It may not look like much, but the plank can’t be beat for building strong abs from the inside out. Discover why a minute spent planking is never wasted!

If you’ve listened to the chatter among fitness professionals over the past few years, you probably heard that crunches shouldn’t make up the bulk of your ab work. This no doubt seemed like blasphemy at first, because most of us have been doing crunches since junior high gym class. So why the change of heart?

Think about it: The chances are good that the majority of your day isn’t spent lifting in the gym. You probably spend most of your time sitting. You sit at a desk. You sit in your car. You sit hunched at your computer or playing Xbox when you’re home. Why would you want to further reinforce that hunched position by constantly crunching in the gym?

I wouldn’t say that you can’t or shouldn’t throw crunches into the mix every now and then. But only doing crunches for your abs is like only bench pressing, with no back or shoulder work. You’ll lose out on some fundamental strength gains, leading to an imbalanced and underdeveloped physique.

So how are you supposed to work your abs without crunches? One of the more popular methods is the old-fashioned plank. Planks are boring, you say? My first response to that is: Are you doing them correctly? The answer, upon official review, is generally no.

However, if you’ve gotten to the point where you can snooze through a two-minute good form plank, then maybe it’s time to spice it up. Luckily, there is a multitude of plank variations that raise the difficulty level. But first let’s discuss what a proper plank should look like.

It’s essential to master the basic front plank before moving on to more advanced variations, because it teaches the foundational cues that make all planking movements effective. And when done consistently and correctly, it will—not can, will—confer strength benefits that improve your big lifts and general athleticism. On the other hand, poor form planking can just end up just aggravating low back problems and not working your abs at all. It’s your choice!

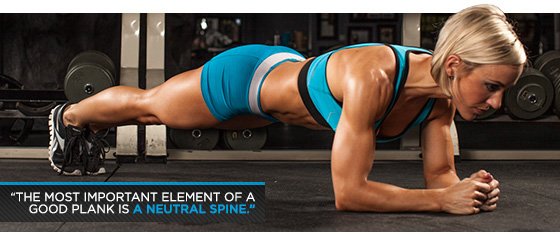

Start off by getting into a plank position: propped on your forearms, elbows in line with your shoulders, and your toes planted firmly. Are you set up? Probably not if you’re reading this, which is fine, because we are just getting started!

The most important element of a good plank is a neutral spine. The most common problem I see in planks is a sinking low back, but the second-most common problem is an arched back with the hips in the air. This is the type of “plank” usually favored by people who say a plank is “too easy.”

Here’s a cue to help you find the right depth. When performing an effective plank you should be able to place a broomstick down your back and the only contact points should be the head, upper back and hips. Well, someone else will probably have to place it there, but you get the idea.

Another element of a good plank is proper shoulder position. Be careful not to shrug the shoulders toward your ears. The final element is head position. Do your best to keep your head neutral, like it is when you stand straight and stare forward. Resist the urge to crane your neck up or let your head droop down. Try staring at your fists to keep good head position.

If you do it right, your body should form a straight line from your head to your ankles. Every one of the cues I mentioned makes it more difficult to do that—which is the point. Allow me to repeat it one more time: Planks are not supposed to be easy.

The basic front plank is an isometric movement, meaning you’ll hold in a static position for a predetermined amount of time. Some people like to work up to holding it for minutes on end—and there’s nothing wrong with that.

However, if you can hold a good form plank for 45-60 seconds without too much quivering and grunting, you have earned the privilege of moving on to more difficult variations, if you want. Just like a standard plank, each of these doesn’t require anything more than your body and an iron will. They’ll feel grueling and unstable at first, but improving at them will train your entire midsection from the inside out.

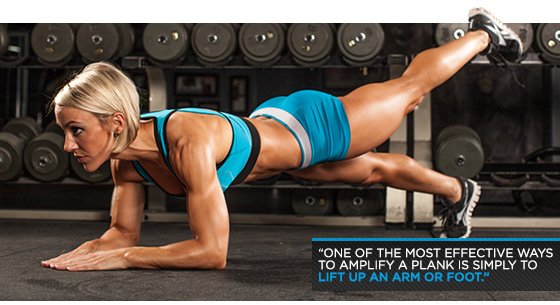

A beautiful thing about planks is that it only takes small changes to make the movement much harder to perform. One of the most effective ways to amplify a plank is simply to lift up an arm or foot. By doing this, your body has to work harder to resist instability and rotational force. Start off by holding a good plank—emphasis on good—with only one foot in contact with the ground, and then progress to lifting an arm up.

When you feel solid on three points of contact, cut back to two: one arm and one leg. If you can hold this for 60-90 seconds with good technique, pat yourself on the back and move on to more advanced versions.

Another modification is to push your arms out in front of you slightly during the hold. The change of leverage from having your arms farther away from your center makes this movement much more awkward and difficult. Go slow with this!

What has become known as the RKC plank—or Russian Kettlebell Challenge plank—is not that visually different from a traditional plank. To the untrained eye the two might even look identical. Here are the differences that make the RKC plank diabolically difficult:

- Arms are placed slightly farther out in front of you.

- Elbows are closer together.

- Quads are flexed.

- Glutes are flexed or clenched as hard as possible.

These steps don’t sound that much more difficult until you try them. The arm and elbow changes reduce your support base, similar to raising an arm. But the real difference is the emphasis on whole-body tension. In an RKC plank, you should flex everything involved as hard as you can—a testament to the high-tension style of the Russian kettlebell community.

Don’t be surprised if you can’t hold an RKC plank for half the time of a standard plank, because it instigates far higher activity in the muscles involved. In analyzing both movements, strength coach and researcher Bret Contreras found that the RKC plank has four times the lower ab, three times the external oblique, and two times the internal oblique activation as a traditionally executed plank. Give it a try if you’re not convinced.

Don’t worry, this isn’t going to turn into one of those “functional training” articles and I won’t suggest anything performed on an inverted BOSU ball. But the truth is that adding an unstable surface to your planks is one of the most challenging and fun variations you can perform.

Pretty much any gym in existence has some stability balls available. So skip the BOSU and place your arms on its larger, less stable cousin while holding your plank.

All the normal plank rules apply: straight line from head to ankles, back not arched either up or down, shoulders not up by ears.

Not difficult enough? No problem. Just remove one foot from the floor as discussed above. The combination of an unstable surface and one less point of contact will make for the most grueling 30 seconds of your life.

Moving your body may seem to go against the basic idea of a plank, since in every other variation you fight to resist that urge. However, there are a couple of dynamic plank variations that belong in the conversation. Both build off the basic plank by emphasizing dynamic stabilization, where you hold a stable position while moving some other part of your body.

For the body saw, set up in a plank position but place your feet on a stability ball or in a suspension trainer. If you don’t have those, you could try furniture sliding pads, or even just a pair of paper plates—seriously!

Once you’re in position, slowly begin moving your body forward and backward using your forearms. Similar to a barbell rollout or ab roller, the movement will become much more difficult the farther your elbows are from the center of your body.

The fallout is similar to the body saw, except that your arms are on the ball or suspension trainer. If using a ball, place your forearms on top like you would for a traditional plank. Next, begin slowly rolling the ball out in front of you, reversing the movement when it becomes too difficult to hold or your lower back feels like it is about to cave. Rolling the ball out just 6-10 inches should do the job.

If you use a suspension trainer you can make the fallout much more difficult, because you have a greater range of possible motion. Grab the handles and follow the same steps as on the ball, pressing your arms out in front of you slowly. If you’re strong enough you might even be able to push the handles all the way out so your arms are totally straight.

If you made it this far, you realize that planks aren’t just a miserable waste of your gym time. Maybe you’ve even thought of another tweak you could make to add a level of instability or difficulty. If you can dream it up, someone has probably given it a name and a YouTube video, so go for it. It might be the best thing you ever did for your abs.